December 2025

Close Up & Fluorescent

Introducing UP’s New Superstar Microscope

- Story by Jessica Murphy Moo

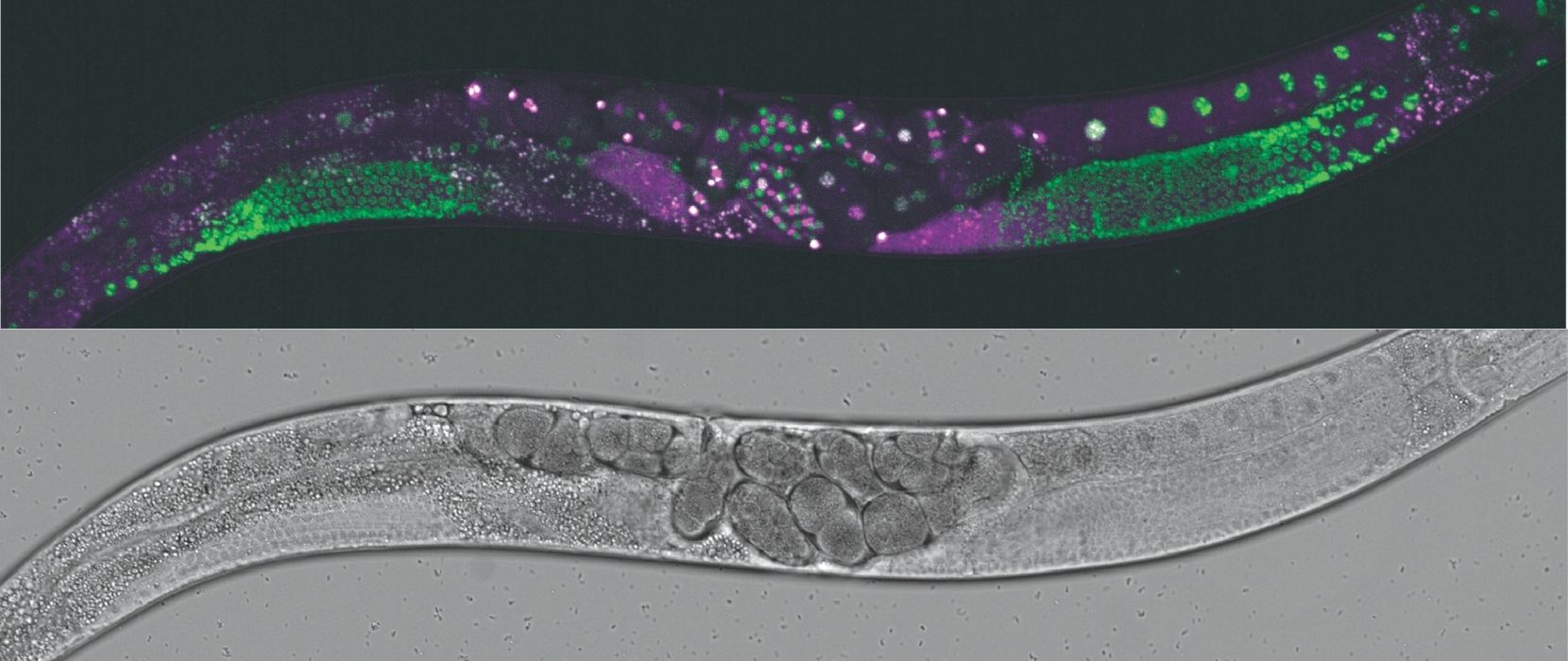

A transparent worm, seen through UP's new game-changing microscope, imaged (bottom) with white light, and also (top) with lasers that allow researchers to see chromosomes going though cell division using fluorescent proteins.

JUST AS SHE’S BEEN DOING for about a year as a research lab assistant, India Rosario ’24 places several minuscule worms on a slide. They’re each about one millimeter in length, the size of the tip of a ballpoint pen. The worms—called C. elegans—have been living on petri dishes surrounded by bacteria, which they also eat.

“Living the dream,” Rosario says.

She puts some agarose on the slide, which is a soft platform to keep the worms still while she examines them under UP’s new microscope. She places a second slide on top, and the worms are pressed into place, cozy in their new location, ready for their close-up. Sometimes the slight pressure of the coverslip makes a few eggs pop out. We spot about five eggs, though the eggs outside the worm aren’t really of interest at the moment. Rosario and biology professor David Wynne are studying the development of the oocytes still inside the worm, observing if chromosomes have separated correctly during meiotic cell division. That these particular worms are transparent—a very rare trait in the animal kingdom—makes it possible to see everything going on inside without the need for dissection. UP’s new microscope is going to help them make gains on their research more quickly.

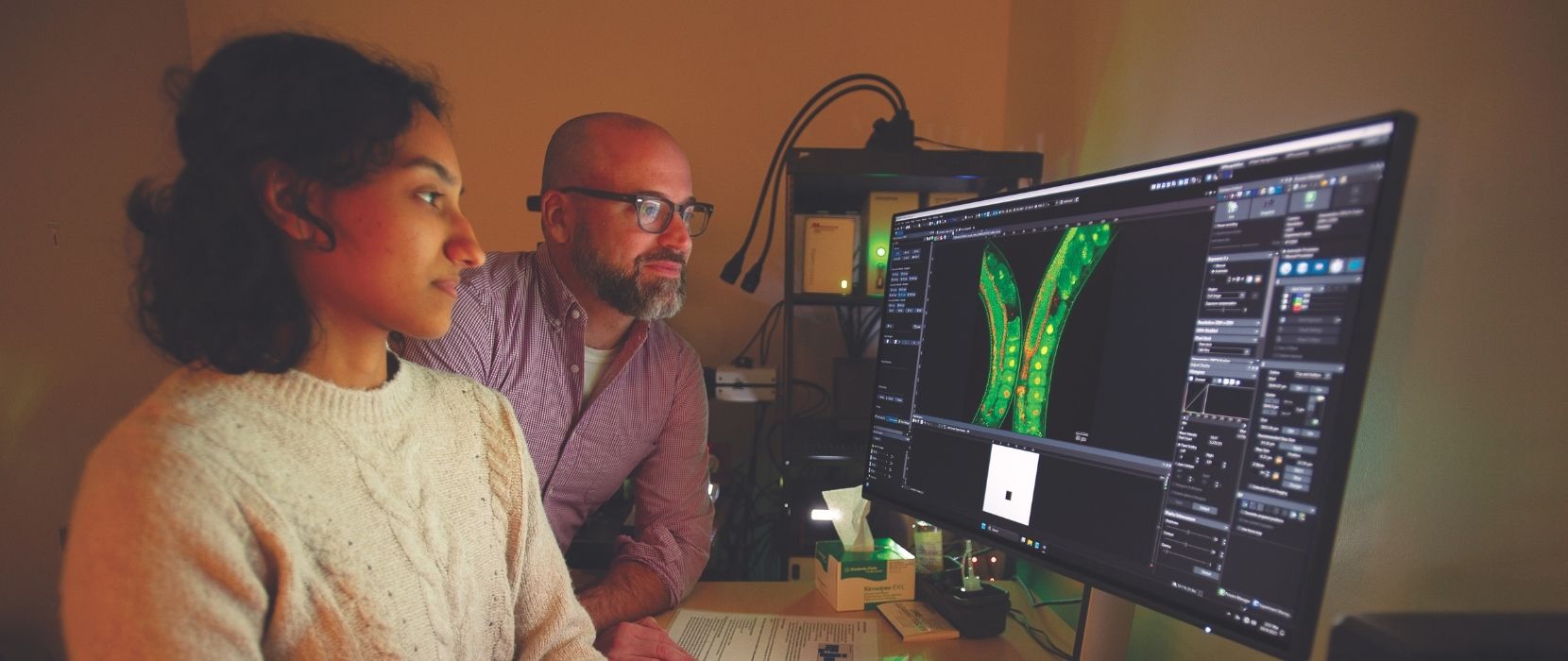

We head over to the microscope to take a look. This new microscope is a superstar, “the ultimate workhorse,” as Wynne calls it, and the cell biologists are thrilled that University of Portland now houses one in Swindells. This type of microscope—a spinning-disk confocal fluorescence microscope—came to University of Portland courtesy of a highly selective NSF Major Research Instrumentation Program grant. Winning this grant, which was about two years in the making, was a huge achievement and amounted to more than $460,000. The microscope has also already provided a reason for labs from at least five area schools to come to a conference at University of Portland this summer and for students and researchers to all receive training on using the confocal microscope for their molecular research.

Before now, UP scientists would have had to head over to OHSU and pay by the hour to use their confocal microscope, and there would be no option for overnight time-lapse data gathering. Now, University of Portland biology professors have options—and their students are gaining loads of lab experience with state-of- the-art equipment that many don’t get access to until grad school.

A 3-D image through the ventricles showing smooth muscle cells (red) and an enzyme that remodels the heart (green)

THE DYER LAB

Professor Laura Dyer is a developmental biologist, and her research focuses on the molecular development of the heart. The heart, the first organ to start functioning, is the only organ that starts to work as it forms, beating and pumping even before it can receive its first lung-oxygenated blood cells. “It’s wild and beautiful,” Dyer says.

She and her team of student researchers are specifically trying to better understand why—as the heart is forming—certain smaller arteries turn into mature coronary arteries, and how blood flow within a particular area of the aorta affects the heart’s formation.

For this research, her mighty lab of three undergrads looks at the hearts of chicken embryos at a very early stage of development. What they learn from these tiny four-chambered hearts can extrapolate to the formation of the human heart.

THE MATTY LAB

Have you ever seen a toddler get “hangry”? You know, that “hungry-angry” combo that presents as moodiness or an all-out meltdown. Adults can get hangry, too. So, it turns out, do the C. elegans nematodes.

Biology professor Molly Matty is interested to know what’s going on in the gut at a molecular level to make hangry behavior happen.

She has done experiments where she has deprived C. elegans of food and asked: If the worms are hungry, do they take on riskier behaviors? (They do.) And she is now looking at how changes in gut bacteria, also known as their microbiome, change the neural signals that lead to decision-making. She gives the worms different types of bacteria, from their run-of-the-mill everyday E. coli to what she calls “fun bacteria” like those extracted from rotting plant matter. By using fluorescent bacteria that show up as different colors, she’ll be able to put the worm under the confocal microscope and see how changes in bacterial abundance or location in the gut sync up with different behaviors.

THE WYNNE LAB

As noted in the opening, professor Dave Wynne and post-baccalaureate researcher India Rosario use C. elegans for their research on chromosome separation. They are also keenly interested in the proteins that ensure the chromosomes separate correctly.

Their focus is on a regulatory protein called Haspin (specifically HASP-1). Rosario has been using CRISPR gene editing technology to target this protein. She has presented at University of Portland’s second annual C. elegans summer conference—aptly called Wormlandia!—and she has also presented at the international C. elegans conference, which this past year was held at UC Davis. In her session, the other presenters were researchers from labs in Germany, Scotland, and China, as well as labs from two other American universities, Harvard and Rockefeller. Not only was Rosario the only presenter from an undergrad institution, her talk put UP on a list next to some of the best-funded research institutes in the US. Not bad for one year out of school. She has found that without HASP-1, the worms end up with chromosomal errors that make their eggs unviable. Using CRISPR, she is now targeting smaller sections of HASP-1, to find the regions of the protein that “trigger” its roles to promote correct separation.

Wynne and Rosario’s lines of inquiry could have impacts on human health: If we understand more about how certain proteins work—why and where one binds to another—this could be useful information for new drugs that target and inhibit certain proteins in chemotherapeutics.

Rosario has found that working in a lab with a supportive mentor is the type of setting she’s interested to continue to work in for her career. She has enjoyed working with the other students working in the Wynne lab, often answering their questions, creating the positive setting that Wynne and her other biology professors have modeled for her. Each of the professors using this confocal microscope are the product of strong mentors and robust undergraduate research programs. This microscope is arming them with new ways to create that same experience for the next generation of scientists.

JESSICA MURPHY MOO is the editor of this magazine.